the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Air quality and acid deposition impacts of local emissions and transboundary air pollution in Japan and South Korea

Yefu Gu

Matthew A. Shapiro

Brent Stephens

Numerous studies have reported that ambient air pollution, which has both local and long-range sources, causes adverse impacts on the environment and human health. Previous studies have investigated the impacts of transboundary air pollution (TAP) in East Asia, albeit primarily through analyses of episodic events. In addition, it is useful to better understand the spatiotemporal variations in TAP and the resultant impact on the environment and human health. This study aimed at assessing and quantifying the air quality impacts in Japan and South Korea due to local emissions and TAP from sources in East Asia - one of the most polluted regions in the world. We applied state-of-the-science atmospheric models to simulate air quality in East Asia and then analyzed the air quality and acid deposition impacts of both local emissions and TAP sources in Japan and South Korea. Our results show that ∼ 30 % of the annual average ambient PM2.5 concentrations in Japan and South Korea in 2010 were contributed to by local emissions within each country, while the remaining ∼ 70 % were contributed to by TAP from other countries in the region. More detailed analyses also revealed that the local contribution was higher in the metropolises of Japan (∼ 40 %–79 %) and South Korea (∼ 31 %–55 %) and that minimal seasonal variations in surface PM2.5 occurred in Japan, whereas there was a relatively large variation in South Korea in the winter. Further, among all five studied anthropogenic emission sectors of China, the industrial sector represented the greatest contributor to annual surface PM2.5 concentrations in Japan and South Korea, followed by the residential and power generation sectors. Results also show that TAP's impact on acid deposition ( and ) was larger than TAP's impact on PM2.5 concentrations (accounting for over 80 % of the total deposition), and that seasonal variations in acid deposition were similar for both Japan and South Korea (i.e., higher in both the winter and summer). Finally, wet deposition had a greater impact on mixed forests in Japan and savannas in South Korea. Given these significant impacts of TAP in the region, it is paramount that cross-national efforts should be taken to mitigate air pollution problems across East Asia.

Air pollution is one of the major environmental problems facing the modern world, leading to adverse impacts on human health (Brook et al., 2004; Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002; Cook et al., 2005; Dockery et al., 1993; Lelieveld et al., 2015; Nel, 2005; Pope III and Dockery, 2006; Samet et al., 2000; Yim and Barrett, 2012; Yim et al., 2013, 2015, 2019a), the environment (Gu et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2005; Rodhe et al., 2002), climate (Guo et al., 2016; Koren et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2018, 2019), and economic costs (Y. J. Lee et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2017). This study focuses specifically on the phenomenon of transboundary air pollution (TAP; Yim et al., 2019b), which creates problems of assigning attribution and thwarts the implementation of effective policies. There is a sense of urgency given the significant implications of TAP on the environment, on human health and on the geographic breadth of the areas affected. Zhang et al. (2017) investigated the health impacts due to global transboundary air pollution and international trade, estimating that ∼ 411 000 deaths worldwide have resulted from TAP, while 762 000 deaths have resulted from international trade-associated emissions. J. Lin et al. (2014) investigated the air pollution in the United States due to the emissions of its international trade in China, estimating air pollution of China contributed to 3 %–10 % and 0.5 %–1.5 % of the annual surface sulfate and ozone concentrations, respectively, in the western United States.

The East Asian region has been suffering from air pollution for decades, especially transboundary air pollution. The extant literature reports significant impacts of TAP in Japan (Aikawa et al., 2010; Kaneyasu et al., 2014; Kashima et al., 2012; Murano et al., 2000), South Korea (Han et al., 2008; Heo et al., 2009; B.-U. Kim et al., 2017; H. C. Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2012, 2009; Koo et al., 2012; S. Lee et al., 2011, 2013; Oh et al., 2015; Vellingiri et al., 2016), or East Asia in general and beyond (Gao et al., 2011; Gu and Yim, 2016; Hou et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2018a, b; Koo et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2016; C.-Y. Lin et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2018; Nawahda et al., 2012; Park et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2017), emphasizing TAP's origins in China. For example, Aikawa et al. (2010) assessed transboundary sulfate () concentrations at various measurement sites across the East Asian Pacific Rim, reporting that China contributed to 50 %–70 % of the total annual in Japan with a maximum in the winter of 65 %–80 %. Murano et al. (2000) examined the transboundary air pollution over two Japanese islands, Oki Island and Okinawa Island, reporting that the high non-sea-salt sulfate concentrations observed in Oki in certain episodic events were associated with the air mass transported from China and South Korea under favorable weather conditions. Focusing on Fukuoka (an upwind area of Japan), Kaneyasu et al. (2014) investigated the impact of transboundary particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter <2.5 µm (PM2.5), concluding that, in northern Kyushu, contributions were greater than those of local air pollution. In terms of China-borne TAP in South Korea, S. Lee et al. (2013, 2011) traced contributors to Seoul's episodic high PM10 and PM2.5 events, showing that a stagnant high-pressure system over the city led to the updraft, transport, and subsequent descent of PM10 and PM2.5 from China to Seoul. While TAP from China in Japan and South Korea was identified, the spatiotemporal variations of TAP and sectoral contributions from emissions from China have yet to be fully understood.

Wet acid deposition due to air pollution is also critically important given the risks to ecosystems. Adverse environmental impacts of wet deposition have been reported in Asia (Bhatti et al., 1992), and specific research has investigated TAP's impact on wet deposition in East Asia (Arndt et al., 1998; Ichikawa et al., 1998; Ichikawa and Fujita, 1995; Lin et al., 2008). Within the East Asian region, Japan and South Korea are particularly vulnerable to acid rain (Bhatti et al., 1992; Oh et al., 2015). Arndt et al. (1998) reported that the contribution of China to sulfur deposition in Japan was 2.5 times higher in winter and spring than in summer and autumn, and that both China and South Korea have been primary contributors to the sulfur deposition in southern and western Japan. Ichikawa et al. (1998) found that TAP accounted for more than 50 % of wet sulfur deposition in Japan. In their investigation of the contribution of energy consumption emissions to wet sulfur deposition in northeast Asia, Streets et al. (1999) identified the impact of nitrogen oxide emissions on the region's acid deposition. Lin et al. (2008) reported that anthropogenic emissions of Japan and the Korean peninsula had a larger contribution to wet nitrogen deposition than to wet sulfur deposition in Japan due to the substantial transportation sources of the two countries. This finding highlights the importance of assessing the contribution of various sectors to acid deposition due to their distinct emission profiles.

To mitigate air pollution in East Asia, it is critical to conduct a more comprehensive evaluation of the contributions of both local emissions and transboundary air pollution sources. Thus, this study assesses the spatiotemporal variations in the contributions of local emissions and transboundary air pollution (from China) to air quality and thus wet deposition in Japan and South Korea. To identify which sectors are the largest contributors to TAP and acid deposition in Japan and South Korea, we conducted a source apportionment analysis of China's sector-specific emissions. The method details of the source apportionment analysis are provided in Sect. 2. Section 3 is divided into two parts: the first part presents model evaluation results and estimates of ambient PM2.5 concentrations and source apportionment, while the second part discusses wet deposition results and its impact on various land covers in Japan and South Korea. A discussion in Sect. 4 concludes this study.

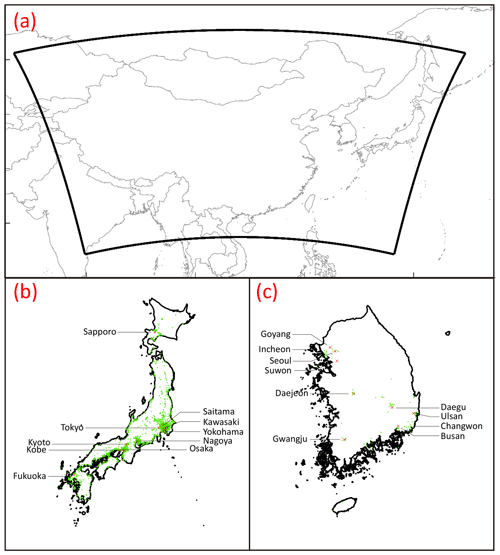

This study applied the state-of-the-science atmospheric models (Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF) and the Community Multiscale Air Quality modeling System, CMAQ) to simulate hourly air quality over Japan and South Korea in the year 2010. The WRF model (Skamarock et al., 2008) was applied to simulate meteorology over the study area with one domain at a spatial resolution of 27 km and 26 vertical layers. Figure 1a depicts the model domain. The 6 h and Final Operational Global Analysis (FNL) data (National Centers for Environmental Prediction et al., 2000) were applied to drive the WRF model, and the land-use data were updated based on Data Center for Resources and Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (RESDC) (Liu et al., 2014).

Figure 1(a) Model simulation domain (solid black line). Monitoring stations (green dots) and major cities (red crosses) with populations ≥ 1 million in (b) Japan and (c) South Korea.

We applied CMAQv4.7.1 (Byun and Schere, 2006) to simulate air quality over East Asia. The boundary conditions were provided by the global chemical transport model (GEOS-Chem) (Bey et al., 2001), while the updated Carbon Bond mechanism (CB05) was used for chemical speciation and reaction regulation. The hourly emissions were compiled based on multiple datasets: the HTAP-V2 dataset (Janssens-Maenhout et al., 2012) was applied for anthropogenic emissions, the FINN 1.5 dataset (Wiedinmyer et al., 2014) was utilized for fire emissions, and the MEGAN-MACC database (Sindelarova et al., 2014) was applied for biogenic emissions. The speciation scheme, temporal profiles, and vertical profiles adopted in our emission inventory were based on Gu and Yim (2016), while plume rise heights for large industry sectors and power plants were based on Briggs (1972). Details of the atmospheric models were further discussed in Gu and Yim (2016).

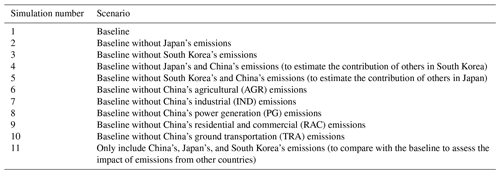

To investigate the contributions of local emissions and transboundary air pollution to air quality and acid deposition over Japan and South Korea, and in particular those originating from China sectoral emissions, a total of 11 1-year simulations were conducted (see Table 1). The first simulation was a baseline case, in which all the emissions were included. Two simulations were performed in which emissions of Japan and South Korea were removed in turn. One simulation was conducted in which emissions of China and South Korea were removed for estimating other countries’ contributions to air pollution in Japan. A similar simulation was also conducted for South Korea in which emissions of China and Japan were removed. Another five simulations were designed to apportion the contribution of various emission sectors of China. Similar to Gu et al. (2018), the sectors were defined as (AGR) agriculture, (IND) industry, (PG) power generation, (RAC) residential and commercial, and (TRA) ground transportation. Emissions of each China sector were removed in turn. The difference in model results between the baseline scenario and other scenarios was used to attribute the contribution of emissions from the respective country or Chinese sector. One additional simulation was performed in which only emissions of China, Japan, and South Korea were included. The differences between the baseline scenario and the last scenario were used to attribute the contribution of emissions from all other countries in the domain except China, Japan, and South Korea.

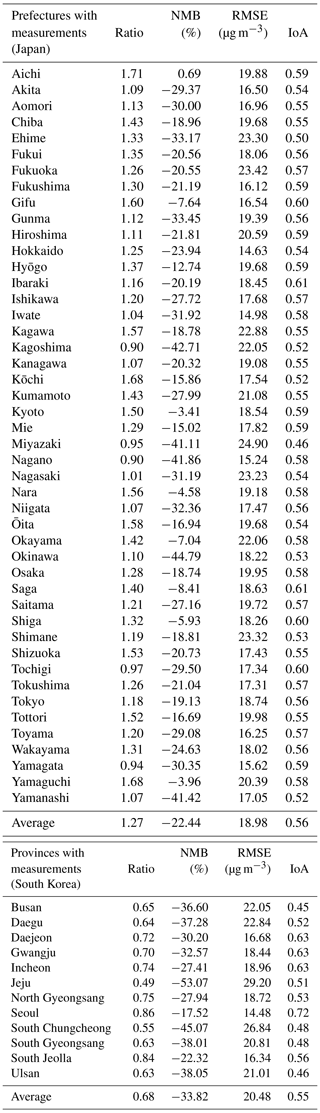

Table 2Model evaluations of PM10 across Japanese prefectures and South Korean provinces where measurements are available. NMB refers to normalized mean bias, RMSE refers to root mean square error, and IoA refers to index of agreement. We note that the evaluation of Japan was based on hourly data, while that of South Korea was based on monthly data.

To examine the model capacity for estimating spatiotemporally varied distribution of PM2.5 in South Korea and Japan, we first employed ground-level respirable suspended particulate (PM10) observation datasets in 2010 from Japan and South Korea to compare with respirable suspended particulates output gathered from our air quality model. Hourly measurements from 1678 valid observation stations in Japan were collected by the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Japan (http://www.nies.go.jp/igreen/, last access: 7 April 2018); monthly measurements from 121 valid observation stations in South Korea were extracted from an annual report of air quality in 2010 (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2011). The locations of monitoring are depicted by the green dots in Fig. 1. Each measurement was compared with model outputs at the particular grid in which the corresponding observation stations are located. To further evaluate the CMAQ performance, we also compared our model results to satellite-retrieved ground-level PM2.5 concentration data, which were fused from MODIS, MISR, and SeaWiFS AOD observations in 2014 (van Donkelaar et al., 2016). We extracted concentration values of satellite-retrieved PM2.5 at the center of each model grid within Japan and South Korea and then conducted grid-to-grid comparisons with annual-averaged model outputs. Model performance was specified by a series of widely used statistical indicators, including ratio (r), normalized mean bias (NMB), root mean square error (RMSE), and index of agreement (IoA). The indicators are calculated as follows:

where M is the model prediction; is model output mean; O is the observation measurement, and is the observation mean.

To facilitate the discussion of model performance, evaluation results for different stations were gathered and averaged by the basic district division in different countries (i.e., prefectures in Japan and provinces in South Korea).

3.1 Model evaluation

We conducted a model evaluation of PM10 to assess our model performance over the prefectures of Japan and over the provincial divisions of South Korea where measurements are available; see Table 2. On average, the annual mean ratio (normalized mean bias, root mean square error) for Japan and South Korea was 1.27 (−22.44 %, 18.98 µg m−3) and 0.68 (−33.82 %, 20.48 µg m−3), respectively. Their mean indexes of agreement were 0.56 and 0.55 for Japan and South Korea, respectively.

These results show that the model tends to underestimate PM, which is consistent with the results reported in other studies (Ikeda et al., 2014; Koo et al., 2012). For example, Koo et al. (2012) conducted an evaluation of CMAQ performance on PM10 over the Seoul and Incheon metropolises as well as the north and south Gyeonggi provinces, showing results similar to ours.

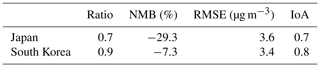

Table 3Statistical results of model evaluation using satellite-retrieval PM2.5 over Japan and South Korea. NMB refers to normalized mean bias, RMSE refers to root mean square error, and IoA refers to index of agreement.

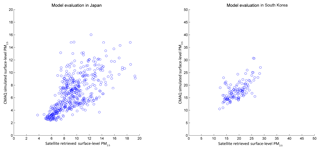

Figure 2 and Table 3 show the model evaluation using satellite-retrieval PM2.5 over Japan and South Korea. The indexes of agreement are 0.7 and 0.8 for Japan and South Korea, respectively, while the normalized mean biases are % and %. Ikeda et al. (2014) reported that their CMAQ model tended to underestimate PM2.5 over Japan with a monthly normalized mean bias of −24.1 % to 66.7 %. The underestimation may be because the model results were an average value over a model grid, while the measurements represented the local PM level at a specific location. Despite the underestimation, our index of agreement results indicate that the model can reasonably capture the PM variability over the two countries.

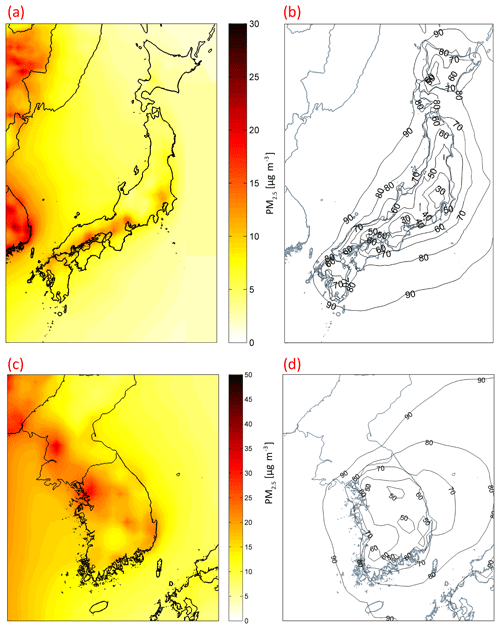

Table 4Model evaluation of acid deposition in Japan and South Korea. NMB refers to the normalized mean bias, RMSE refers to root mean square error, and IoA refers to index of agreement.

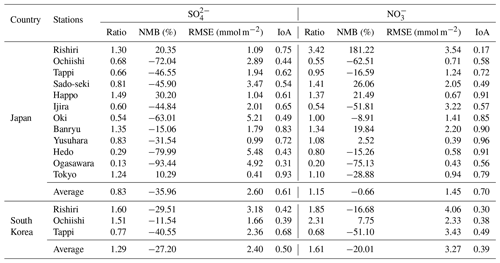

Figure 3The modeled annual average surface PM2.5 (µg m−3) over (a) Japan and (c) South Korea in 2010 and the percentage (%) of total PM2.5 due to transboundary air pollution over (b) Japan and (d) South Korea.

and deposition simulated by CMAQ has been compared with monthly ground-level measurements from the Acid Deposition Monitoring Network in East Asia (EANET) (https://monitoring.eanet.asia/document/public/index, last access: 20 August 2018). The evaluation results are shown in Table 4. and tend to be underestimated in Japan and South Korea, which may be associated with simulation bias of PM2.5 concentration. Normalized mean biases of and ranged from −93.44 % to 30.20 % and −75.13 % to 181.22 % in Japan, respectively, while they ranged from −40.55 % to −11.54 % and −51.10 % to 7.75 % in South Korea. The averaged index of agreement and ratio of and NO3 indicate that our model could basically capture the fluctuation and magnitude of acid deposition in Japan and South Korea. A slightly better performance in Japan was observed.

3.2 Annual and seasonal ambient PM2.5 in Japan and South Korea

Figure 3a and c show the annual average surface PM2.5 over Japan and South Korea, respectively. The annual average surface PM2.5 concentration over Japan was 5.91 µg m−3, while that over South Korea was 16.90 µg m−3. Higher PM2.5 concentrations occurred in metropolises: in Japan, higher PM2.5 levels occurred in Nagoya (13.48 µg m−3), Osaka (12.07 µg m−3), and Saitama (9.36 µg m−3). Higher PM2.5 levels were also observed at Okayama (14.78 µg m−3), even though its population is not as large as the aforementioned metropolises, which may be due to its substantial industrial emissions in the region. In South Korea, higher PM2.5 levels occurred in Incheon (23.90 µg m−3), Goyang (27.05 µg m−3), Seoul (30.64 µg m−3), and Suwon (30.75 µg m−3). Two additional high annual average levels of PM2.5 can be identified in non-metropolis areas, which may also be due to their relatively high industrial emissions.

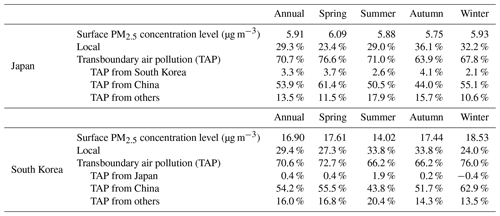

Table 5Annual and seasonal surface PM2.5 concentration levels (µg m−3) and source countries' contributions to PM2.5 (%) in Japan and South Korea.

In Japan, seasonal variations in surface PM2.5 did not vary significantly, ranging from 5.75 to 6.09 µg m−3. In South Korea, however, seasonal variations were relatively larger. The winter surface PM2.5 level was 18.53 µg m−3, while the next highest levels occurred in spring (17.61 µg m−3) and autumn (17.44 µg m−3). The lowest level of PM2.5 occurred in summer (14.02 µg m−3) in South Korea.

3.3 Local and transboundary contributions

Table 5 shows the contributions of emissions of different source countries to PM2.5 in different receptor countries. On average, approximately 29 % of annual ambient PM2.5 in both Japan and South Korea was contributed to by local emissions, while approximately 71 % was identified as TAP. Of TAP's contribution, China was the key contributor, accounting for approximately 54 % of the annual surface PM2.5 in both Japan and South Korea. The results of our analysis of the contributions of PM2.5 between Japan and South Korea show that South Korea accounted for 3.3 % of the annual surface PM2.5 in Japan, whereas Japan's contribution to PM2.5 in South Korea was marginal (0.4 %). The contribution of other countries was non-negligible (i.e., 13.5 % in Japan and 16.0 % in South Korea).

Figure 3b and d indicate that the local contribution was relatively higher in the metropolises of Japan (40.2 %–78.6 %) and South Korea (31.4 %–55.2 %), which is due to greater proportions of emissions being generated by local industry, transportation, and power generation. In Japan, the western areas showed a higher TAP contribution than the eastern areas, while, in South Korea, the western and northern areas showed a higher TAP contribution than other areas.

The TAP contribution varied with seasons. In Japan, the highest relative TAP contribution occurred in spring (76.6 %), followed by summer (71.0 %) and winter (67.8 %). The lowest relative contribution occurred in autumn (63.9 %). In South Korea, the highest relative contribution of TAP occurred in winter (76.0 %) and spring (72.7 %), while the lowest occurred in summer (66.2 %) and autumn (66.2 %). Seasonal variations in TAP were most likely due to varying emissions and prevailing wind directions across seasons.

Table 6Annual and seasonal contributions of Chinese sectoral emissions to surface PM2.5 (µg m−3) in Japan and South Korea. Emission sectors include agriculture (AGR), power generation (PG), ground transportation (TRA), industrial (IND), and residential and commercial (RAC). Agriculture refers to agriculture and agricultural waste burning; power generation refers to electricity generation; ground transportation refers to road transportation, rail, pipelines, and inland waterways; industrial refers to energy production other than electricity generation, industrial processes, solvent production and application, and residential and commercial refers to heating, cooling, equipment, and waste disposal or incineration related to buildings.

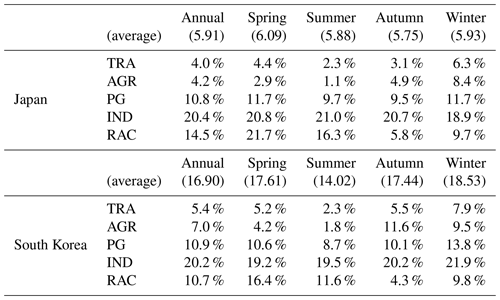

3.4 Transboundary air pollution from China sectoral emissions

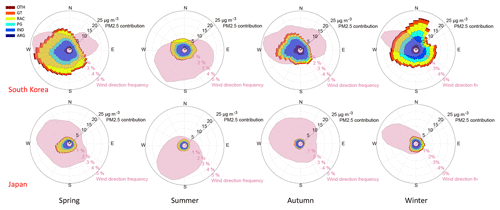

As shown in Table 6, among Chinese sectors, industrial emissions were a key contributor to annual surface PM2.5 in both Japan and South Korea, accounting for approximately one-fifth of annual average concentrations. As well, there was a little seasonal variance in terms of its contribution to Japan's and South Korea's PM2.5 levels, which may be because industrial emissions from China remain relatively constant all year long. For both Japan and South Korea, the second- and third-most contributors to annual surface PM2.5 were the residential and commercial (RAC) sector and the power generation (PG) sector, respectively. Unlike the industrial sector, seasonal variations in relative contributions for these two sectors were apparent. Figure 4 shows that the southerly wind in Japan and South Korea during spring and summer provided favorable conditions for pollutant transport of the Chinese RAC sector. We observed contributions of China's RAC sector to be 12 %–22 % of the surface PM2.5 in Japan and South Korea in spring and summer. In autumn, the relative contribution of the Chinese RAC sector was minimal due to the northerly wind that was not favorable for TAP from China. In spring and winter, the northwesterly wind was favorable for transporting pollutants from northern China, in which emissions from PG were substantial. The remaining Chinese contribution was from the ground transportation and agriculture sectors. When combined, both sectors accounted for 8 % and 12 % of the annual surface PM2.5 in Japan and South Korea, respectively, with a maximum relative contribution in autumn and winter.

3.5 Effects of acid deposition

3.5.1 Annual and seasonal variations

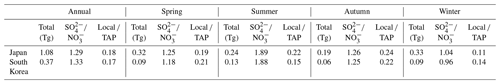

Table 7 presents the annual and seasonal acid deposition in Japan and South Korea. We estimated that outdoor air pollution resulted in 1.08 and 0.37 Tg of acid deposition annually in Japan and South Korea, respectively. The local ∕ TAP ratios were estimated to be 0.18 and 0.17 for Japan and South Korea, respectively, which is lower than the respective ratios for PM2.5 concentrations, highlighting TAP's larger impact on acid deposition. We note that PM2.5 concentrations include both primary and secondary PM2.5 species, while acid deposition focuses on and , which are secondary species. As well, local sources may contribute disproportionately more primary PM2.5 species, i.e., black carbon. Given that the annual ratio values were greater than 1 for both Japan and South Korea, sulfur emissions can be considered as a key contributor to acid deposition.

Table 7Annual and seasonal acid deposition ( and ) (Tg) in Japan and South Korea, including and local ∕ TAP (transboundary air pollution) contribution ratios.

The seasonal variation in acid deposition between Japan and South Korea was similar: higher in winter and summer and lower in autumn and spring. For Japan, the largest TAP occurred in winter and the smallest TAP occurred in autumn. For South Korea, the largest and smallest TAP occurred in winter and spring, respectively. Regarding the ratio, the seasonal variation in Japan and South Korea suggests that deposition was more important in summer and less important in the winter. For Japan, the value of these ratios ranged from 1.04 to 1.89; for South Korea they ranged from 0.96 to 1.88. It should be noted that the ratio is particularly lower in winter than in other seasons. Given minor local contributions, we conclude that TAP NOx was significant in winter. Similar to the annual ratios, the seasonal ratios highlight the significant sulfate deposition in the two countries.

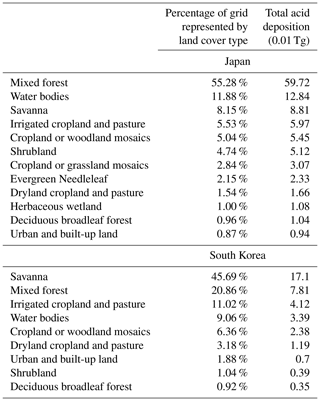

Table 8Percentage of land coverage (%) and air pollution-induced acid deposition (0.01 Tg) across various land cover types in Japan and South Korea. A total of 24 land cover types provided by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) were considered, including urban and built-up land; dryland cropland and pasture; irrigated cropland and pasture; mixed dryland or irrigated cropland and pasture; cropland or grassland mosaics; cropland or woodland mosaics; grassland; shrubland; mixed shrubland or grassland; savanna; deciduous broadleaf forest; deciduous needleleaf forest; evergreen broadleaf; evergreen needleleaf; mixed forest; water bodies; herbaceous wetland; wooden wetland; barren or sparsely vegetated; herbaceous tundra; wooded tundra; mixed tundra; bare ground tundra; snow or ice. The land covers with no acid deposition on them are not listed.

3.5.2 Acid deposition over various land covers

To assess acid deposition impact over various land cover types, Table 8 shows the percentage of each land cover type in Japan and South Korea along with its air pollution-induced acid deposition. We note that the land cover percentage refers to the percentage of the model grids that were dominated by each land cover type. For Japan, the land cover distribution shows that the most prevalent land covers (> 5 %) are mixed forest, water bodies, savanna, irrigated cropland and pasture, and cropland or woodland mosaics. These land covers, when combined, account for ∼ 87 % of the land in Japan. Urban and built-up land occupies only ∼ 1 % of the land. In terms of the impact of acid deposition in the ecosystem in Japan, total deposition over mixed forest was 0.60 Tg, which may result in direct damage to trees and soil. In urban and built-up land, the acid deposition was estimated to be 0.01 Tg, representing ∼ 1 % of the total Japanese acid deposition.

For South Korea, the most prevalent land cover types are savanna, mixed forest, irrigated cropland and pasture, water bodies, and cropland or woodland mosaics. Together, they account for ∼ 93 % of the land, while urban and built-up land account for ∼ 2 % of the land. The acid depositions over the savanna and mixed forest were estimated to be 0.17 and 0.08 Tg, respectively. These two land covers share more than 66 % of the total acid deposition in the country. Acid deposition on urban and built-up land was 0.01 Tg, which is comparable to that in Japan.

This study estimated the contributions of both local sources and TAP from Asia on surface PM2.5 in Japan and South Korea. Our findings were consistent with those reported by other studies (Aikawa et al., 2010; Koo et al., 2012). Among various emission sectors of China, our results show that, particularly with favorable prevailing wind, China's industrial emissions were the major contributor (∼ 20 %) to surface PM2.5 as well as to acid deposition in Japan and South Korea. Our estimated wet deposition ratios of and were still higher than 1.00, implying the need for further control of SO2 emissions, particularly from China's industrial sector. Previous studies have reported a downward trend of deposition in East Asia in recent years due to substantial SO2 emissions reductions in China (Itahashi et al., 2018; Seto et al., 2004).

In addition, wet deposition had significant impacts on mixed forests in Japan and the savanna in South Korea. It is noted that the dominant soils in Japan and South Korea have a low acid buffering capacity (Yagasaki et al., 2001). Acid deposition-attributable forest diebacks have been reported in Japan (Izuta, 1998; Nakahara et al., 2010) and South Korea (Lee et al., 2005). High acid deposition may cause soil acidification and eutrophication, which are particularly harmful in pH-sensitive areas such as forest and savanna. Despite the fact that N deposition may increase soil N availability and hence photosynthetic capacity and plant growth in an environment with a low N availability (Bai et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2007; Xia et al., 2009), excessive N would suppress or damage plant growth (Fang et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2009; Mo et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009) and also reduce biodiversity (Bai et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2006).

In our analysis, we further revealed that higher TAP contributions from Asia occurred in spring in Japan and in winter in South Korea due to the favorable weather conditions in the two seasons. While emissions of East Asia are projected to decline (Wang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2014), weather and climate may play a more important role under future climate change (Guo et al., 2019). Given the fact that summer and winter monsoons were weakening (Wang and He, 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Wang and Chen, 2016; Yang et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2012), the frequency of favorable weather conditions for TAP from Asia is projected to decrease, and TAP may be reduced subsequently.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the significance of transboundary air pollution affecting Japan and South Korea as well as the impact of wet deposition on various land covers. In this way, this study provides a critical reference for atmospheric scientists to understand transboundary air pollution and for policymakers to formulate effective emission control policies, emphasizing the significance of cross-country emission control policies.

Air pollution measurements of Japan and South Korea are available at http://www.nies.go.jp/igreen/ (last access: 7 April 2018) provided by the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Japan (NIES, 2018) and at http://library.me.go.kr/search/DetailView.Popup.ax?cid=5506169 (last access: 12 June 2018) provided by the National Institute of Environmental Research of South Korea (NIER, 2018). Deposition measurements are available at https://monitoring.eanet.asia/document/public/index (last access: 20 August 2018) provided by the Acid Deposition Monitoring Network in East Asia (EANET, 2018). Emission data for air quality modeling were provided by openly accessible data including HTAP-V2 (Janssens-Maenhout et al., 2012), FINN 1.5 dataset (Wiedinmyer et al., 2014), and the MEGAN-MACC database (Sindelarova et al., 2014). The speciation scheme, temporal profiles, and vertical profiles adopted in our emission inventory were based on Gu and Yim (2016). Satellite-retrieved surface PM2.5 concentrations from MODIS, MISR and SeaWiFS Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) are openly available at https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/sdei-global-annual-gwr-pm2-5-modis-misr-seawifs-aod/data-download (last access: 16 April 2018, van Donkelaar et al., 2018). The 6 h FNL operational model global tropospheric analyses are available at https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds083.2/ (last access: 28 July 2014, National Centers for Environmental Prediction, 2014). The land cover data in China are available upon request through the database at http://www.resdc.cn/data.aspx?DATAID=99 (last access: 16 April 2014, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2018).

SHLY planned the research and sought funding to support this study. SHLY conducted the analyses with technical support from YG. SHLY wrote the paper with discussions with all the co-authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department and the Hong Kong Observatory for providing air quality and meteorological data, respectively. We acknowledge the support of the CUHK Central High Performance Computing Cluster, on which computation was performed for this work.

This research has been supported by the Vice-Chancellor's Discretionary Fund of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (grant no. 4930744).

This paper was edited by Xiaohong Liu and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Aikawa, M., Ohara, T., Hiraki, T., Oishi, O., Tsuji, A., Yamagami, M., Murano, K., and Mukai, H.: Significant geographic gradients in particulate sulfate over Japan determined from multiple-site measurements and a chemical transport model: Impacts of transboundary pollution from the Asian continent, Atmos. Environ., 44, 381–391, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.10.025, 2010.

Arndt, R. L., Carmichael, G. R., and Roorda, J. M.: Seasonal source: Receptor relationships in Asia, Atmos. Environ., 32, 1397–1406, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00241-0, 1998.

Bai, Y., Wu, J., Clark, C. M., Naeem, S., Pan, Q., Huang, J., Zhang, L., and Han, X.: Tradeoffs and thresholds in the effects of nitrogen addition on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: evidence from inner Mongolia Grasslands, Glob. Change Biol., 16, 358–372, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01950.x, 2010.

Bey, I., Jacob, D. J., Yantosca, R. M., Logan, J. A., Field, B. D., Fiore, A. M., Li, Q., Liu, H. Y., Mickley, L. J., and Schultz, M. G.: Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 106, 23073–23095, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000807, 2001.

Bhatti, N., Streets, D. G., and Foell, W. K.: Acid rain in Asia, Environ. Manage., 16, 541–562, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02394130, 1992.

Briggs, G. A.: Chimney plumes in neutral and stable surroundings, Atmos. Environ., 6, 507–510, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(72)90120-5, 1972.

Brook, R. D., Franklin, B., Cascio, W., Hong, Y., Howard, G., Lipsett, M., Luepker, R., Mittleman, M., Samet, J., Smith, S. C., and Tager, I.: Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: A statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association, Circulation, 109, 2655–2671, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8, 2004.

Brunekreef, B. and Holgate, S. T.: Air pollution and health, Lancet, 360, 1233–1242, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8, 2002.

Byun, D. and Schere, K. L.: Review of the Governing Equations, Computational Algorithms, and Other Components of the Models-3 Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) Modeling System, Appl. Mech. Rev., 59, 51–77, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2128636, 2006.

Chinese Academy of Sciences: Land cover data in China in 2010, Resource and Environment Data Cloud Platform, available at: http://www.resdc.cn/data.aspx?DATAID=99, last access: 16 April 2014.

Cook, A. G., Weinstein, P., and Centeno, J. A.: Health Effects of Natural Dust: Role of Trace Elements and Compounds, Biol. Trace Elem. Res., 103, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1385/BTER:103:1:001, 2005.

Dockery, D. W., Pope, C. A., Xu, X., Spengler, J. D., Ware, J. H., Fay, M. E., Ferris, B. G., and Speizer, F. E.: An Association between Air Pollution and Mortality in Six U.S. Cities, N. Engl. J. Med., 329, 1753–1759, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199312093292401, 1993.

EANET: Acid deposition in East Asia, Acid Deposition Monitoring Network in East Asia, available at: https://monitoring.eanet.asia/document/public/index, last access: 20 August 2018.

Fan, H. B., Liu, W. F., Li, Y. Y., Liao, Y. C., and Yuan, Y. H.: Tree growth and soil nutrients in response to nitrogen deposition in a subtropical Chinese fir plantation, Acta Ecol. Sin., 27, 4630–4642, 2007.

Fang, Y., Gundersen, P., Mo, J., and Zhu, W.: Nitrogen leaching in response to increased nitrogen inputs in subtropical monsoon forests in southern China, For. Ecol. Manag., 257, 332–342, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.09.004, 2009.

Gao, Y., Liu, X., Zhao, C., and Zhang, M.: Emission controls versus meteorological conditions in determining aerosol concentrations in Beijing during the 2008 Olympic Games, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 12437–12451, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-12437-2011, 2011.

Gu, Y. and Yim, S. H. L.: The air quality and health impacts of domestic trans-boundary pollution in various regions of China, Environ. Int., 97, 117–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.004, 2016.

Gu, Y., Wong, T. W., Law, S. C., Dong, G. H., Ho, K. F., Yang, Y., and Yim, S. H. L.: Impacts of sectoral emissions in China and the implications: air quality, public health, crop production, and economic costs, Environ. Res. Lett., 13, 084008, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aad138, 2018.

Guo, J., Deng, M., Lee, S. S., Wang, F., Li, Z., Zhai, P., Liu, H., Lv, W., Yao, W., and Li, X.: Delaying precipitation and lightning by air pollution over the Pearl River Delta. Part I: Observational analyses, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 6472–6488, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023257, 2016.

Guo, J., Xu, H., Liu, L., Chen, D., Peng, Y., Yim, S. H. L., Yang, Y., Li, J., Zhao, C., and Zhai, P.: The trend reversal of dust aerosol over East Asia and the North Pacific Ocean attributed to large-scale meteorology, deposition and soil moisture, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 124, online first, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030654, 2019.

Guo, X., Wang, R., Chang, R., Liang, X., Wang, C., Luo, Y., Yuan, Y., and Guo, W.: Effects of nitrogen addition on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Acer truncatum seedlings, Dendrobiology, 72, 151–161, https://doi.org/10.12657/denbio.072.013, 2014.

Han, Y.-J., Kim, T.-S., and Kim, H.: Ionic constituents and source analysis of PM2.5 in three Korean cities, Atmos. Environ., 42, 4735–4746, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.01.047, 2008.

Heo, J.-B., Hopke, P. K., and Yi, S.-M.: Source apportionment of PM2.5 in Seoul, Korea, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4957–4971, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4957-2009, 2009.

Hou, X., Chan, C. K., Dong, G. H., and Yim, S. H. L.: Impacts of transboundary air pollution and local emissions on PM2.5 pollution in the Pearl River Delta region of China and the public health, and the policy implications, Environ. Res. Lett., 14, 034005, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaf493, 2018.

Ichikawa, Y. and Fujita, S.: An analysis of wet deposition of sulfate using a trajectory model for East Asia, Water. Air. Soil Pollut., 85, 1927–1932, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01186116, 1995.

Ichikawa, Y., Hayami, H., and Fujita, S.: A Long-Range Transport Model for East Asia to Estimate Sulfur Deposition in Japan, J. Appl. Meteorol., 37, 1364–1374, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1998)037<1364:ALRTMF>2.0.CO;2, 1998.

Ikeda, K., Yamaji, K., Kanaya, Y., Taketani, F., Pan, X., Komazaki, Y., Kurokawa, J., and Ohara, T.: Sensitivity analysis of source regions to PM 2.5 concentration at Fukue Island, Japan, J. Air Waste Manag., 64, 445–452, https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2013.845618, 2014.

Itahashi, S., Yumimoto, K., Uno, I., Hayami, H., Fujita, S.-I., Pan, Y., and Wang, Y.: A 15-year record (2001–2015) of the ratio of nitrate to non-sea-salt sulfate in precipitation over East Asia, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 2835–2852, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-2835-2018, 2018.

Izuta, T.: Ecophysiological responses of Japanese forest tree species to ozone, simulated acid rain and soil acidification, J. Plant Res., 111, 471–480, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02507781, 1998.

Janssens-Maenhout, G., Dentener, F., Van Aardenne, J., Monni, S., Pagliari, V., Orlandini, L., Klimont, Z., Kurokawa, J. I., Akimoto, H., Ohara, T., Wankmueller, R., Battye, B., Grano, D., Zuber, A., and Keating, T.: EDGAR-HTAP: a Harmonized Gridded Air Pollution Emission Dataset Based on National Inventories, EUR – Scientific and Technical Research Reports, Publications Office of the European Union, available at: http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC68434 (last access: 1 June 2015), 2012.

Kaneyasu, N., Yamamoto, S., Sato, K., Takami, A., Hayashi, M., Hara, K., Kawamoto, K., Okuda, T., and Hatakeyama, S.: Impact of long-range transport of aerosols on the PM2.5 composition at a major metropolitan area in the northern Kyushu area of Japan, Atmos. Environ., 97, 416–425, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2014.01.029, 2014.

Kashima, S., Yorifuji, T., Tsuda, T., and Eboshida, A.: Asian dust and daily all-cause or cause-specific mortality in western Japan, Occup. Environ. Med., 69, 908–915, https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2012-100797, 2012.

Kim, B.-U., Bae, C., Kim, H. C., Kim, E., and Kim, S.: Spatially and chemically resolved source apportionment analysis: Case study of high particulate matter event, Atmos. Environ., 162, 55–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.05.006, 2017.

Kim, H. C., Kim, E., Bae, C., Cho, J. H., Kim, B.-U., and Kim, S.: Regional contributions to particulate matter concentration in the Seoul metropolitan area, South Korea: seasonal variation and sensitivity to meteorology and emissions inventory, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 10315–10332, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-10315-2017, 2017.

Kim, H.-S., Kim, D.-S., Kim, H., and Yi, S.-M.: Relationship between mortality and fine particles during Asian dust, smog–Asian dust, and smog days in Korea, Int. J. Environ. Health Res., 22, 518–530, https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2012.667796, 2012.

Kim, Y. J., Woo, J.-H., Ma, Y.-I., Kim, S., Nam, J. S., Sung, H., Choi, K.-C., Seo, J., Kim, J. S., Kang, C.-H., Lee, G., Ro, C.-U., Chang, D., and Sunwoo, Y.: Chemical characteristics of long-range transport aerosol at background sites in Korea, Atmos. Environ., 43, 5556–5566, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2009.03.062, 2009.

Koo, Y.-S., Kim, S.-T., Yun, H.-Y., Han, J.-S., Lee, J.-Y., Kim, K.-H., and Jeon, E.-C.: The simulation of aerosol transport over East Asia region, Atmos. Res., 90, 264–271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2008.03.014, 2008.

Koo, Y.-S., Kim, S.-T., Cho, J.-S., and Jang, Y.-K.: Performance evaluation of the updated air quality forecasting system for Seoul predicting PM10, Atmos. Environ., 58, 56–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2012.02.004, 2012.

Koren, I., Altaratz, O., Remer, L. A., Feingold, G., Martins, J. V., and Heiblum, R. H.: Aerosol-induced intensification of rain from the tropics to the mid-latitudes, Nat. Geosci., 5, 118–122, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1364, 2012.

Lai, I.-C., Lee, C.-L., and Huang, H.-C.: A new conceptual model for quantifying transboundary contribution of atmospheric pollutants in the East Asian Pacific rim region, Environ. Int., 88, 160–168, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.018, 2016.

Lee, C. H., Lee, S.-W., Kim, E.-Y., Jeong, J.-H., Cho, H.-J., Park, G.-S., Lee, C.-Y., and Jeong, Y.-H.: Effects of Air Pollution and Acid Deposition on Three Pinus densiflora (Japanese Red Pine) Forests in South Korea, J. Agric. Meteorol., 60, 1153–1156, https://doi.org/10.2480/agrmet.1153, 2005.

Lee, S., Ho, C.-H., and Choi, Y.-S.: High-PM10 concentration episodes in Seoul, Korea: Background sources and related meteorological conditions, Atmos. Environ., 45, 7240–7247, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.08.071, 2011.

Lee, S., Ho, C.-H., Lee, Y. G., Choi, H.-J., and Song, C.-K.: Influence of transboundary air pollutants from China on the high-PM10 episode in Seoul, Korea for the period October 16–20, 2008, Atmos. Environ., 77, 430–439, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.05.006, 2013.

Lee, Y. J., Lim, Y. W., Yang, J. Y., Kim, C. S., Shin, Y. C., and Shin, D. C.: Evaluating the PM damage cost due to urban air pollution and vehicle emissions in Seoul, Korea, J. Environ. Manage., 92, 603–609, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.09.028, 2011.

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D., and Pozzer, A.: The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale, Nature, 525, 367–71, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15371, 2015.

Li, Z., Niu, F., Fan, J., Liu, Y., Rosenfeld, D., and Ding, Y.: Long-term impacts of aerosols on the vertical development of clouds and precipitation, Nat. Geosci., 4, 888–894, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1313, 2011.

Lin, C.-Y., Zhao, C., Liu, X., Lin, N.-H., and Chen, W.-N.: Modelling of long-range transport of Southeast Asia biomass-burning aerosols to Taiwan and their radiative forcings over East Asia, Tellus B, 66, 23733, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v66.23733, 2014.

Lin, J., Pan, D., Davis, S. J., Zhang, Q., He, K., Wang, C., Streets, D. G., Wuebbles, D. J., and Guan, D.: China's international trade and air pollution in the United States., P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 1736–41, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1312860111, 2014.

Lin, M., Oki, T., Bengtsson, M., Kanae, S., Holloway, T., and Streets, D. G.: Long-range transport of acidifying substances in East Asia – Part II: Source–receptor relationships, Atmos. Environ., 42, 5956–5967, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.03.039, 2008.

Liu, J., Kuang, W., Zhang, Z., Xu, X., Qin, Y., Ning, J., Zhou, W., Zhang, S., Li, R., and Yan, C.: Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns, and causes of land-use changes in China since the late 1980s, J. Geogr. Sci., 24, 195–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-014-1082-6, 2014.

Liu, Z., Yim, S. H. L., Wang, C., and Lau, N. C.: The Impact of the Aerosol Direct Radiative Forcing on Deep Convection and Air Quality in the Pearl River Delta Region, Geophys. Res. Lett., 45, 4410–4418, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL077517, 2018.

Liu, Z., Ming, Y., Wang, L., Bollasina, M., Luo, M., Lau, N. C., and Yim, S. H. L.: A Model Investigation of Aerosol-Induced Changes in the East Asian Winter Monsoon, Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, online first, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL084228, 2019.

Lu, X., Mo, J., Gilliam, F. S., Zhou, G., and Fang, Y.: Effects of experimental nitrogen additions on plant diversity in an old-growth tropical forest, Glob. Change Biol., 16, 2688–2700, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02174.x, 2010.

Lu, X.-K., Mo, J.-M., Gundersern, P., Zhu, W.-X., Zhou, G.-Y., Li, D.-J., and Zhang, X.: Effect of Simulated N Deposition on Soil Exchangeable Cations in Three Forest Types of Subtropical China, Pedosphere, 19, 189–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(09)60108-9, 2009.

Luo, M., Hou, X., Gu, Y., Lau, N.-C., and Yim, S. H.-L.: Trans-boundary air pollution in a city under various atmospheric conditions, Sci. Total Environ., 618, 132–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.001, 2018.

Mo, J., Li, D., and Gundersen, P.: Seedling growth response of two tropical tree species to nitrogen deposition in southern China, Eur. J. For. Res., 127, 275–283, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-008-0203-0, 2008.

Murano, K., Mukai, H., Hatakeyama, S., Suk Jang, E., and Uno, I.: Trans-boundary air pollution over remote islands in Japan: observed data and estimates from a numerical model, Atmos. Environ., 34, 5139–5149, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00319-8, 2000.

Nakahara, O., Takahashi, M., Sase, H., Yamada, T., Matsuda, K., Ohizumi, T., Fukuhara, H., Inoue, T., Takahashi, A., Kobayashi, H., Hatano, R., and Hakamata, T.: Soil and stream water acidification in a forested catchment in central Japan, Biogeochemistry, 97, 141–158, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-009-9362-4, 2010.

National Centers for Environmental Prediction, National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Department of Commerce: NCEP FNL Operational Model Global Tropospheric Analyses, continuing from July 1999, Research Data Archive, The National Center for Atmospheric Research, Computational and Information Systems Laboratory, Boulder, CO, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6M043C6, 2000.

National Centers for Environmental Prediction: 6-hour FNL operational model global tropospheric analyses, available at: https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds083.2/, last access: 28 July 2014.

National Institute of Environmental Research: Annual Report of Ambient Air Quality in Korea, 2010, Ministry of Environment, available at: http://library.me.go.kr/search/DetailView.Popup.ax?cid=5506169 (last access: 12 June 2018), 2011.

Nawahda, A., Yamashita, K., Ohara, T., Kurokawa, J., and Yamaji, K.: Evaluation of Premature Mortality Caused by Exposure to PM2.5 and Ozone in East Asia: 2000, 2005, 2020, Water. Air. Soil Pollut., 223, 3445–3459, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-012-1123-7, 2012.

Nel, A.: Air pollution-related illness: effects of particles, Science, 308, 804–806, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1108752, 2005.

NIER: Ground-level Air pollution measurements of South Korea, National Institute of Environmental Research of South Korea, available at: http://library.me.go.kr/search/DetailView.Popup.ax?cid=5506169, last access: 12 June 2018.

NIES: Ground-level Air pollution measurements of Japan, National Institute for Environmental Studies in Japan, available at: http://www.nies.go.jp/igreen/, last access: 7 April 2018.

Oh, H.-R., Ho, C.-H., Kim, J., Chen, D., Lee, S., Choi, Y.-S., Chang, L.-S., and Song, C.-K.: Long-range transport of air pollutants originating in China: A possible major cause of multi-day high-PM10 episodes during cold season in Seoul, Korea, Atmos. Environ., 109, 23–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.03.005, 2015.

Park, J., Ryu, J., Kim, D., Yeo, J., and Lee, H.: Long-Range Transport of SO2 from Continental Asia to Northeast Asia and the Northwest Pacific Ocean: Flow Rate Estimation Using OMI Data, Surface in Situ Data, and the HYSPLIT Model, Atmosphere, 7, 53, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos7040053, 2016.

Pope III, C. A. and Dockery, D. W.: Health Effects of Fine Particulate Air Pollution: Lines that Connect, J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc., 56, 709–742, https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485, 2006.

Rodhe, H., Dentener, F., and Schulz, M.: The Global Distribution of Acidifying Wet Deposition, Environ. Sci. Technol., 36, 4382–4388, https://doi.org/10.1021/es020057g, 2002.

Samet, J. M., Dominici, F., Curriero, F. C., Coursac, I., and Zeger, S. L.: Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality in 20 U.S. Cities, 1987–1994, N. Engl. J. Med., 343, 1742–1749, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200012143432401, 2000.

Seto, S., Hara, H., Sato, M., Noguchi, I., and Tonooka, Y.: Annual and seasonal trends of wet deposition in Japan, Atmos. Environ., 38, 3543–3556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.03.037, 2004.

Sindelarova, K., Granier, C., Bouarar, I., Guenther, A., Tilmes, S., Stavrakou, T., Müller, J.-F., Kuhn, U., Stefani, P., and Knorr, W.: Global data set of biogenic VOC emissions calculated by the MEGAN model over the last 30 years, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 9317–9341, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-9317-2014, 2014.

Skamarock, W. C., Klemp, J. B., Dudhi, J., Gill, D. O., Barker, D. M., Duda, M. G., Huang, X.-Y., Wang, W., and Powers, J. G.: A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Version 3, Tech. Rep., 113, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6DZ069T, 2008.

Streets, D. G., Carmichael, G. R., Amann, M., and Arndt, R. L.: Energy Consumption and Acid Deposition in Northeast Asia, Ambio, 28, 135–143, 1999.

Tong, C. H. M., Yim, S. H. L., Rothenberg, D., Wang, C., Lin, C. Y., Chen, Y. D., and Lau, N. C.: Projecting the impacts of atmospheric conditions under climate change on air quality over Pearl River Delta region, Atmos. Environ., 193, 79–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.08.053, 2018a.

Tong, C. H. M., Yim, S. H. L., Rothenberg, D., Wang, C., Lin, C. Y., Chen, Y., and Lau, N. C.: Assessing the Impacts of Seasonal and Vertical Atmospheric Conditions on Air Quality over the Pearl River Delta Region, Atmos. Environ., 180, 69–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.02.039, 2018b.

van Donkelaar, A., Martin, R. V., Brauer, M., Hsu, N. C., Kahn, R. A., Levy, R. C., Lyapustin, A., Sayer, A. M., and Winker, D. M.: Global Estimates of Fine Particulate Matter using a Combined Geophysical-Statistical Method with Information from Satellites, Models, and Monitors, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 3762–3772, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05833, 2016.

van Donkelaar, A., R. V. Martin, M. Brauer, N. C. Hsu, R. A. Kahn, R. C. Levy, A. Lyapustin, A. M. Sayer, and D. M. Winker: Satellite-retrieved surface PM2.5 concentrations from MODIS, MISR and SeaWiFS Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD), DOI: 10.7927/H4ZK5DQS, 2018.

Vellingiri, K., Kim, K.-H., Lim, J.-M., Lee, J.-H., Ma, C.-J., Jeon, B.-H., Sohn, J.-R., Kumar, P., and Kang, C.-H.: Identification of nitrogen dioxide and ozone source regions for an urban area in Korea using back trajectory analysis, Atmos. Res., 176–177, 212–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2016.02.022, 2016.

Wang, H. and He, S.: Weakening relationship between East Asian winter monsoon and ENSO after mid-1970s, Chin. Sci. Bull., 57, 3535–3540, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-012-5285-x, 2012.

Wang, H.-J. and Chen, H.-P.: Understanding the recent trend of haze pollution in eastern China: roles of climate change, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 4205–4211, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-4205-2016, 2016.

Wang, H.-J., Chen, H.-P., and Liu, J.: Arctic Sea Ice Decline Intensified Haze Pollution in Eastern China, Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 8, 1–9, 2015.

Wang, M. Y., Yim, S. H. L., Wong, D. C., and Ho, K. F.: Source contributions of surface ozone in China using an adjoint sensitivity analysis, Sci. Total Environ., 662, 385–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.116, 2019.

Wang, S. X., Zhao, B., Cai, S. Y., Klimont, Z., Nielsen, C. P., Morikawa, T., Woo, J. H., Kim, Y., Fu, X., Xu, J. Y., Hao, J. M., and He, K. B.: Emission trends and mitigation options for air pollutants in East Asia, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 6571–6603, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-6571-2014, 2014.

Wiedinmyer, C., Yokelson, R. J., and Gullett, B. K.: Global Emissions of Trace Gases, Particulate Matter, and Hazardous Air Pollutants from Open Burning of Domestic Waste, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 9523–9530, https://doi.org/10.1021/es502250z, 2014.

Xia, J., Niu, S., and Wan, S.: Response of ecosystem carbon exchange to warming and nitrogen addition during two hydrologically contrasting growing seasons in a temperate steppe, Glob. Change Biol., 15, 1544–1556, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01807.x, 2009.

Xu, G.-L., Mo, J.-M., Zhou, G.-Y., and Fu, S.-L.: Preliminary Response of Soil Fauna to Simulated N Deposition in Three Typical Subtropical Forests, Pedosphere, 16, 596–601, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(06)60093-3, 2006.

Xu, X., Han, L., Luo, X., Liu, Z., and Han, S.: Effects of nitrogen addition on dissolved N2O and CO2, dissolved organic matter, and inorganic nitrogen in soil solution under a temperate old-growth forest, Geoderma, 151, 370–377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.05.008, 2009.

Yagasaki, Y., Chishima, T., Okazaki, M., Jeon, D.-S., Yoo, J.-H., and Kim, Y.-K.: Acidification of Red Pine Forest Soil Due to Acidic Deposition in Chunchon, Korea, in: Acid rain 2000: Proceedings from the 6th International Conference on Acidic Deposition: Looking back to the past and thinking of the future, Tsukuba, Japan, 10–16 December 2000, Volume III/III Conference Statement Plenary and Keynote Papers, edited by: Satake, K., Shindo, J., Takamatsu, T., Nakano, T., Aoki, S., Fukuyama, T., Hatakeyama, S., Ikuta, K., Kawashima, M., Kohno, Y., Kojima, S., Murano, K., Okita, T., Taoda, H., Tsunoda, K., and Tsurumi, M., Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1085–1090, 2001.

Yang, J. E., Lee, W.-Y., Ok, Y. S., and Skousen, J.: Soil nutrient bioavailability and nutrient content of pine trees (Pinus thunbergii) in areas impacted by acid deposition in Korea, Environ. Monit. Assess., 157, 43–50, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-008-0513-1, 2009.

Yang, Y., Zheng, X., Gao, Z., Wang, H., Wang, T., Li, Y., Lau, G. N. C., and Yim, S. H. L.: Long-Term Trends of Persistent Synoptic Circulation Events in Planetary Boundary Layer and Their Relationships with Haze Pollution in Winter Half-Year over Eastern China, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 123, 10991–11007, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD028982, 2018.

Yang, Y., Yim, S. H. L., Haywood, J., Osborne, M., Chan, J. C. S., Zeng, Z., and Cheng, J. C. H.: Characteristics of Heavy Particulate Matter Pollutions over Hong Kong and Their Relationships with Vertical Wind Profiles Using High-Time-Resolution Doppler Lidar Measurements, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 124, online first, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD031140, 2019.

Yim, S. H. L. and Barrett, S. R. H.: Public Health Impacts of Combustion Emissions in the United Kingdom, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 4291–4296, https://doi.org/10.1021/es2040416, 2012.

Yim, S. H. L., Stettler, M. E. J., and Barrett, S. R. H.: Air Quality and Public Health Impacts of UK Airports. Part II: Impacts and Policy Assessment, Atmos. Environ., 67, 184–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.10.017, 2013.

Yim, S. H. L., Lee, G. L., Lee, I. H., Allroggen, F., Ashok, A., Caiazzo, F., Eastham, S. D., Malina, R., and Barrett, S. R. H.: Global, regional and local health impacts of civil aviation emissions, Environ. Res. Lett., 10, 034001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/3/034001, 2015.

Yim, S. H. L., Wang, M. Y., Gu, Y., Yang, Y., Dong, G. H., and Li, Q.: Effect of Urbanization on Ozone and Resultant Health Effects in the Pearl River Delta Region of China, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., accepted, 2019a.

Yim, S. H. L., Hou, X., Guo, J., and Yang, Y.: Contribution of local emissions and transboundary air pollution to air quality in Hong Kong during El Niño-Southern Oscillation and heatwaves, Atmos. Res., 218, 50–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2018.10.021, 2019b.

Yin, H., Pizzol, M., and Xu, L.: External costs of PM2.5 pollution in Beijing, China: Uncertainty analysis of multiple health impacts and costs, Environ. Pollut., 226, 356–369, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.029, 2017.

Zhang, Q., Jiang, X., Tong, D., Davis, S. J., Zhao, H., and Geng, G.: Transboundary health impacts of transported global air pollution and international trade, Nat. Publ. Group, 543, 705–709, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21712, 2017.

Zhao, Y., Zhang, J., and Nielsen, C. P.: The effects of energy paths and emission controls and standards on future trends in China's emissions of primary air pollutants, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 8849–8868, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-8849-2014, 2014.

Zhu, J., Liao, H., and Li, J.: Increases in aerosol concentrations over eastern China due to the decadal-scale weakening of the East Asian summer monsoon, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L09809, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051428, 2012.